Fashion forward

How could advanced bio-based materials influence fashion?

The fashion industry is one of the world’s largest polluters, with global carbon emission estimates of between 2-8%, according to the UN Environmental Programme. While 20% of global clean water pollution is caused by dyeing and treating textiles, cited the European Parliament in 2024.

Over half of fashion’s environmental footprint comes from its raw materials, according to a Fashion for Good 2020 report on The state of circular innovations in the indian fashion and textile industry, so the industry is unlikely to meet its climate pledges without sourcing more sustainable alternatives.

The rapid growth of ‘fast fashion’ since its emergence in the 1990s has meanwhile driven the industry to push for cheaper production, leading to offshoring of manufacturing alongside a boom in synthetic materials used for fibres, coatings, pigments and adhesives.

Today, the Guardian reports as few as 3% of clothes worn in the UK are manufactured domestically in Manufacturing’s coming home: UK fashion boss champions ‘reshoring’. Fossil-fuel-derived synthetic materials that dominate the industry include imitation leathers, posing significant environmental and health risks.

Polyester and polyamide, for example, made up more than 60% of global fibre production in 2023 (according to Textile Exchange’s Materials Market report), equivalent to 71Mt. They shed plastic microfibres during washing, daily wear and recycling.

An Environmental International paper titled Microplastics in human blood: polymer types, concentrations and characterisation using μFTIR show these microfibres pollute water sources, harm ecosystems and have even been found in human bloodstreams.

Not to mention, it is estimated that the preferred raw materials demand-and-supply gap in fashion will rise to as much as 133Mt in 2030, according to a BCG Group report on Sustainable raw materials will drive profitability for fashion and apparel brands.

Before the existence of global trade, societies used local available resources as efficiently as possible, leaving minimal waste. Leather emerged as an effective use of animal hides – a readily available by-product of the meat industry.

While animal-derived leather remains a durable material, it raises ethical concerns, requires vast agricultural land and contributes heavily to methane emissions from livestock. Processing leathers is also resource-intensive, with the tanning process resulting in millions of tonnes of toxic tannery sludge each year.

The emerging frontier of bio-based materials therefore presents manufacturers with a dual opportunity – to forge more resilient supply chains in an increasingly turbulent geopolitical climate and to champion innovations in an increasingly stringent regulatory landscape.

The bio-based material industry, and specifically microbially derived products, can be optimised for locally available resources from regenerative biomass, ever more important given the recent global trading uncertainty. The production of these materials can be cleaner than petrochemicals, employing green chemistry and processes that could demonstrate true circularity.

The challenge for emerging leather alternatives is to match the technical properties of animal leather while demonstrating a scaleable production solution that enables price parity. The fact that 76% of consumers intend to shop consciously, yet only 38% do, according to the Conscious consumer report 2025, emphasises the necessity of minimising sustainability price premiums.

Besides the sustainable benefits of using bio-based materials, they demonstrate a structural hierarchy that cannot be easily replicated synthetically. Structural hierarchy refers to a material’s microstructural organisation across multiple scales, from nano- to macroscale, where functional properties at each scale contribute to the overall material properties and performance.

To use a structural hierarchy effectively, it is important to first understand the required performance characteristics of a material across various applications.

Material composition 101

Leather handbags, alongside larger bags, need to balance a good tensile strength with rigidity, durability to withstand everyday abrasion and some level of water repellency. While stricter regulation on furnishings/furniture mandate a good flame retardancy.

Shoes, on the other hand, need to demonstrate good breathability and a higher flexural performance, using techniques such as Bally or Vamp flex.

Beyond these performance characteristics, commercial product ranges need to demonstrate seasonal variation.

Animal leather has evolved to meet these requirements successfully. Leather exhibits a structural hierarchy of woven fibre bundles composed of stacked collagen fibres, ranging from the nanoscale tropocollagen molecule (300nm) to collagen fibres a few millimetres in length.

Chrome tanning is then used to crosslink the collagen fibre matrix, giving leather its distinctive soft and supple haptic with a tuneable stiffness. If the natural patina is not desirable,

a polyurethane (PU) top-coat is added to aid durability and give colour optionality.

Plastic leathers, commonly referred to as ‘vegan leather’, use a structural textile backing coated with an embossed PU or PVC top-coat. The drape of the material is governed by the backing material choice, with floppy knitted materials commonly used for clothing, and cost-efficient non-wovens used in trainers.

The top-coat’s properties can be modified using multiple layers, plasticisers, crosslinkers and fillers, but fundamentally they do not exhibit the structural hierarchy found in leathers and bio-based materials.

The challenge facing most alternative leathers is therefore finding a suitable replacement for the PU top-coat. While bio-based PU has been demonstrated at the lab scale, the vast majority is still petrochemical derived.

First movers

A range of new bio-engineered leather alternatives are emerging in the market, mirroring both the layering approach of plastic leathers and the structural hierarchy of animal leather.

There are increasing examples in the wider textile space of scaled plant-derived materials. Man-made cellulosic fibres, such as lyocell derived from wood pulp, offer a significant water saving on the 10,000L of water required to produce 1kg of cotton fabric. These backers can be coated with bio-PU, made from partially bio-based content instead of fully petroleum-derived, to give a leather appearance and the abrasion resistance that animal leathers are known for.

Other fibre sources are also emerging. Spanish firm Ananas Anam is extracting fibres from waste pineapple leaves, processing them into a non-woven material, also with a bio-PU coating.

Similar approaches have seen local sources of regenerated biomass, such as bananas, being used to boost economic growth.

Common threads

In contrast to the fixed biological structure of an animal hide, the hierarchical structure of bio-engineered materials can be significantly tuned through processing conditions, feedstocks and post-processing techniques. This allows for a degree of control over the final material properties that surpasses the limitations imposed by the inherent animal hide quality.

While each material is based on a different technology and uses proprietary formulations, there are common threads woven into their design.

A structural fibre network provides tensile strength and tear resistance, often enhanced by crosslinking to improve network cohesion. Plasticisers are introduced into the fibre matrix to increase the spacing between fibrous chains, imparting flexibility and softness.

A coating’s density may be controlled through the strategic incorporation of fillers or blowing agents. A range of other additives, including colourants, UV stabilisers, antimicrobials, flame retardants and water repellents further tailor the material’s performance and aesthetics.

Finally, a water-repellent top-coat, such as a wax finish, can be added, aiding the abrasion resistance of the surface.

The microstructure of these materials has many similarities. However, they can broadly be divided into three categories based on material origins.

Plant-derived (fibres, fillers, rubber and cellulose)

There are many examples of naturally occurring polymers that have become the building blocks of leather alternatives. Natural fibre welding combines natural rubber, agricultural waste (such as cork dust or coconut husk) with a patented crosslinker to form sheets of leather-like material.

Arda Biomaterials, UK, repurposes protein-rich spent grain from breweries and distilleries, extracting the proteins and organising them into collagen-like fibril networks.

While Vegea, which is already available at scale, reduces the amount of bio-PU needed in plastic leather, by drying and powderising wine production waste (grape skins, seeds and stalks) to incorporate as a filler.

Fungi-grown

Mycelium-based leathers are an emerging class of bio-based materials derived from fungi, with leading manufacturers like Mycoworks having raised US$125mln in 2022 to help build a production facility.

The root-like structure of a fungus, known as hyphae, grows a complex, 3D-entangled network around a substrate such as sawdust that provides nutrients and a physical matrix. The hyphae network contains a structural hierarchy of rigid chitin fibres with a crosslinked glucan matrix, surrounded by proteins and lipids that act as a natural plasticiser.

The density and interfibrillar bonding of the fibre architecture can be tuned by careful control of the composition of the growth substrate, processing conditions or additional post-processing steps, such as pressing or chemical processing with plasticisers or crosslinkers.

Mycelium-based materials demonstrate potential in high-volume production for textiles, insulation and packaging, but the production is a static tray-based process instead of continuous manufacturing. The process remains expensive due to the sterile growing conditions, with variability in feedstocks risking batch-to-batch variation in the products.

This leads us onto a third category of microbially derived materials produced in a bioreactor, a key driver for cost reduction and scalability.

Microbially derived polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), nano-cellulose, collagen proteins

Many of the ingredients mentioned, like chitin, collagen and cellulose, exist naturally in plants or animals, and can alternatively be produced by nature’s smallest engineers – microorganisms.

The same everyday bacteria that are found in fermented foods and probiotics can be engineered to reproducibly grow nanoscale materials with a variety of biomass sources in a bioreactor. The exact strain of microorganism can be selected based upon the yield and purity of the material made.

Microbially derived materials are emerging across multiple industries, from the sequencing of new high-softness proteins for fibre production, to the production of PHA bioplastics for packaging and animal-free collagen for use in cosmetics.

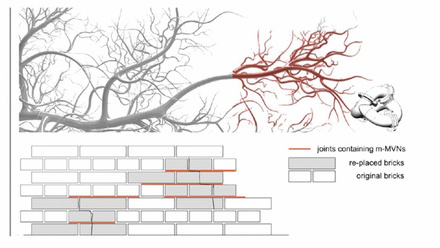

UK based Modern Synthesis has developed an alternative to the traditionally PU top-coat using bacterial cellulose (BC). Cellulose derived from plants can be mechanically and chemically processed down to produce nanocellulose fibres, but a high-purity nanocellulose can also be fermented by bacteria such as K. Rhaeticus – the same bacterial strain used in kombucha tea.

The fermentation-derived polymer forms fibres that are billionths of a metre wide. At that scale, the fibres are eight times stronger than steel, and their nanoscale fibril network encapsulates additional ingredients to achieve new material forms, functions and feels.

The nanocellulose is combined with other bio-based ingredients to alter the haptics of the bio top-coat. This can be combined with a natural textile backing to make a composite material and finished with natural coatings to enhance the water-repellent properties.

Also, microbially derived materials can be modified to add extra functionality to the materials.

As a proof of concept, Modern Synthesis has collaborated with academics at Imperial College London, UK, to modify the microbes to co-produce melanin – a natural pigment found in skin and animal leather, giving the fermented cellulose a naturally black colour.

The natural colour of the nanocellulose top-coat produced by Modern Synthesis is closer to being transparent, offering interesting applications in fashion and textiles not previously possible with opaque natural materials.

The scaling challenge

Scaleability of bio-based materials has long been a barrier to entry, with raw material cost and production rate delaying their widespread adoption. Supply chains in the fashion industry can be complex and brands require materials that reliably ‘drop in’ to their material suppliers’ manufacturing lines without adding further risks or cost.

Microbially derived materials can enable this drop-in approach. The fermentation process presents a simpler route compared to the extraction of chitin, collagen and cellulose from plants and animals, which often require multiple separation stages adding cost.

After all, the food industry is already using fermentation as a low-cost, high-volume production method.

A vast array of ingredients from vinegar and cider through to vitamins and sweeteners are produced through fermentation.

Just as the historic textiles industry took leather as a by-product of the meat industry, bio-based materials are now repurposing the waste of the agricultural sector to fuel the next material revolution.

Microbially derived materials consume less water in production, another key driver of scaleability. With optimised microbe strains and growth media, studies have shown 1kg dry yield of BC from as little as 10L of water, as referenced in the BMC Biotechnology article on Optimized culture conditions for bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter senegalensis MA1.

The dyeing uptake is also less water intensive for BC compared to plant-based cellulose. The nanoscale fibrous structure exhibits a high-surface-area, nanoscale, fibrous structure, ensuring good dye-fibre interactions.

Modern Synthesis’ materials can be engineered to serve their intended lifespan and then offer safer pathways for degradation or material recovery. Numerous studies have demonstrated the process of breaking down BC using natural enzymes to individual sugars (glucose). This is particularly exciting as these sugars can directly be used as the feedstock for the bacteria used to grow BC, or other microbially derived materials, demonstrating true circularity of material from cradle to grave.

One shoe to fit them all

Footwear is one of fashion’s most complex product categories. A running shoe typically requires more than 30 distinct material inputs that are often synthetic in origin, which presents challenges at the end of a product’s life.

The Korvaa Consortium comprises Modern Synthesis, Ecovative, Ourobio and Photino Science Communications. They made the Korvaa concept shoe, combining three biomaterial technologies in one design – a mycelium sole (Ecovative) grown around a 3D-printed, polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) scaffold (Ourobio), with a bacterial nanocellulose shoe upper (Modern Synthesis).

Overall, significant progress has been made in bio-based material fibre development, colouration and coatings over the past decade, but further development is still needed for water-repellent top-coats, edge paints and speciality finishes.

As more innovators emerge in the textiles space, it might seem as though we are industrialising biology. However, biology is inherently the ultimate distributed manufacturing platform and, instead, we can view this movement as a profound biologisation of industry.

Successfully applying engineering biology in fashion would have a significant impact on the UK economy. Enabling and supporting fashion’s transition to the bioeconomy would reinvigorate the declining UK leather and textiles industries. It would also encourage re-onshoring of higher-value manufacturing, shorten supply chains for critical resources, and thus improve resilience.

New lease of life

Second-hand clothing sales are predicted to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 10%, with an estimated value of US$367bln by 2029 indicating a desire for long-lasting, durable products, according to ThredUp’s Resale report 2025.

Indeed, online retailer for second-hand goods, Vinted, is now reportedly the number one clothing retailer in France.

However, without a significant shift in consumer behaviour, most clothes still end up in landfill, around 92Mt globally each year, according to waste management company Business Waste.

UK NGO WRAP recently issued a stark warning. 'If the UK’s used textile sector goes under, charities, local authorities and consumers will have to pay the cost of dealing with unwanted used textiles.'

It highlights that UK textile collectors and sorters pay out £88mln every year to deal with worn-out clothes and home textiles. The cost was previously balanced out by the money they made on reuseable items, but this is no longer the case – there are fewer reusable items that are desirable in global second-hand markets. Most businesses are currently operating at a loss and out of public service.

WRAP has identified three connected solutions to protect the UK’s used textiles sector and maximise use of worn-out textiles – advanced sorting and pre-processing facilities, a redesign of retailer take-back schemes and Extended Producer Responsibility as a key enabler for circularity.

It points to the ACT UK project, involving 18 partners across the textile value chain. The aim is to establish a blueprint for innovative advanced sorting and pre-processing facilities to bridge the gap between worn-out textiles and unlocking textile recycling, to keep resources at a higher value and contributing to the economy.

Sorted textiles have a higher value because they are fibre-sorted and pre-processed to recyclers’ specifications.

By creating a network of 14, 25,000t-capacity per year, advanced sorting and pre-processing facilities in the UK, it is estimated that the cost for collecting and sorting worn-out clothing would be reduced by around half by 2035.