Natural rubber that resists cracking

A way to produce natural rubber that retains its stretchiness and durability while resisting cracking has been cracked, say researchers in the US.

The team from Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) says their rubber is 10 times stronger and four times better at resisting slow crack growth during repeated stretching.

Derived from natural rubber latex, a milk-like substance from the Hevea tree, rubber is harvested, coagulated, dried into a solid, mixed with additives, shaped and heated to trigger vulcanisation. Because long polymer chains result in high viscosity and are difficult to process, the material is typically masticated to break the chains and reduce viscosity. This process creates short polymer chains within the material that are densely crosslinked, or chemically bonded.

The researchers have adapted the process to achieve a gentler transformation that avoids mastication, so the rubber retains long polymer chains, resembling tangled spaghetti. The ‘tanglemer’ is what imbues the rubber with heightened durability as the entanglements outnumber the crosslinks.

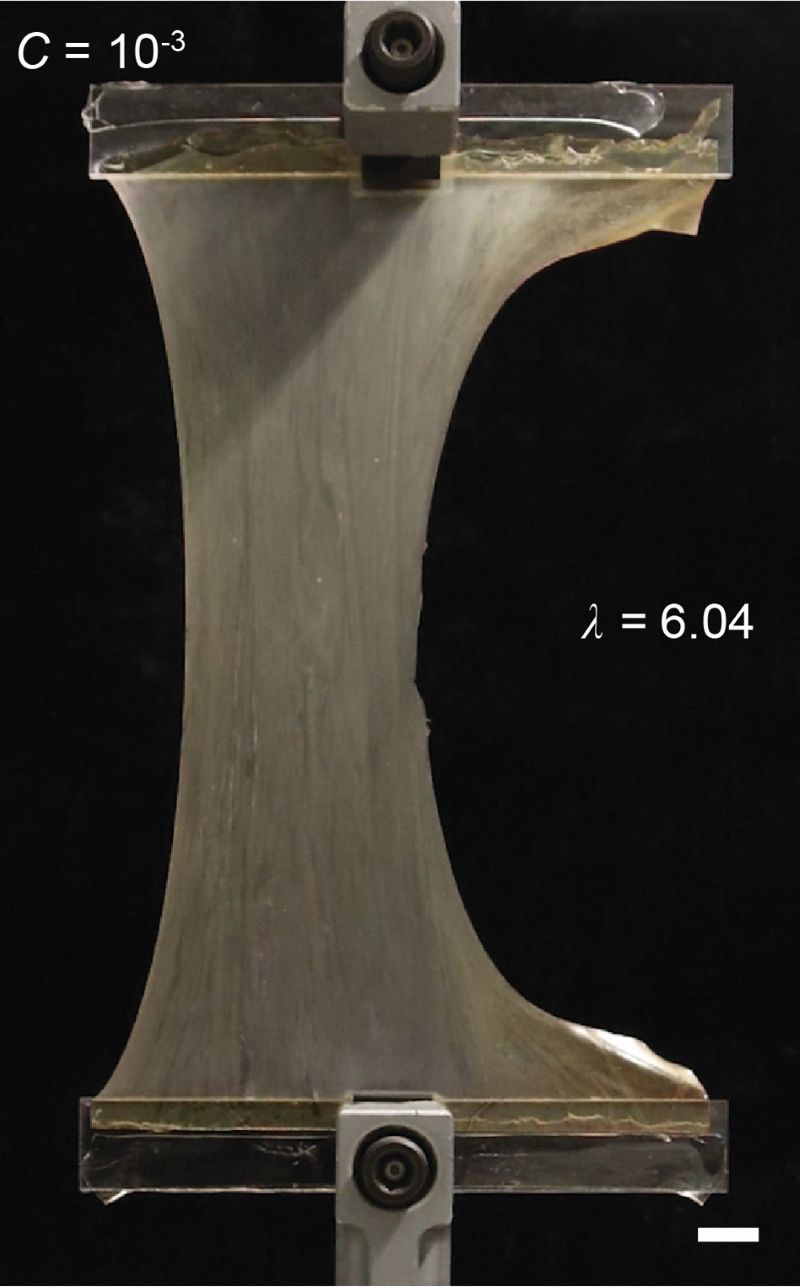

When a crack forms in the new material, the long spaghetti strands spread out the stress by sliding past each other, allowing more rubber to crystallise as it stretches, and overall making the material stronger and more resistant to cracking, explain the researchers.

First author and former SEAS postdoctoral researcher, Guodong Nian, compares this to normal rubber that has a short-chain network (crosslink density of 10−2). The new rubber has a long-chain network crosslink density of 10−3 and reportedly increases the fatigue threshold from approximately 50Jm−2 to around 200Jm−2, and the toughness from ~104Jm−2 to ~105Jm−2.

The team specifically explored processing methods to preserve these long polymer chains, as per the Lake-Thomas model that suggests a long-chain network provides a high fatigue threshold. Having previously studied synthetic latexes to retain long chains, they have applied the principle to natural rubber.

'We used a low-intensity processing method, based on latex processing methods, that preserved the long polymer chains,' Nian says.

The natural latex is mixed with a curing agent solution before being dried into a solid, and then hot-pressed to form a long-chain, highly entangled network. They use the curing agent dicumyl peroxide (DP) and toluene as a solvent to dissolve the natural latex, but only in small amounts. The toluene evaporates during drying, and the DP is activated during hot pressing to crosslink the rubber chains.

Nian notes the overall time is roughly comparable between the two methods of rubber manufacture. They also use less heat during mixing, although require similar temperatures for curing.

However, Nian acknowledges their processing method uses a large amount of water evaporation and yields a smaller volume than would be desirable for products like tyres.

'During the mixing stage, the rubber content is approximately 30% by weight, and the water content is about 60%,' Nian explains. 'We evaporate the water at room temperature in a laboratory fume hood. Nearly all of the rubber is retained throughout the process, resulting in minimal material loss.'

The team believes the material is better suited to thin products like gloves or condoms, and could be viable for flexible electronics or soft robotics parts.