Mass timber could reduce hospital acquired infections

Investigations reveal potential in how wood materials handle bacteria.

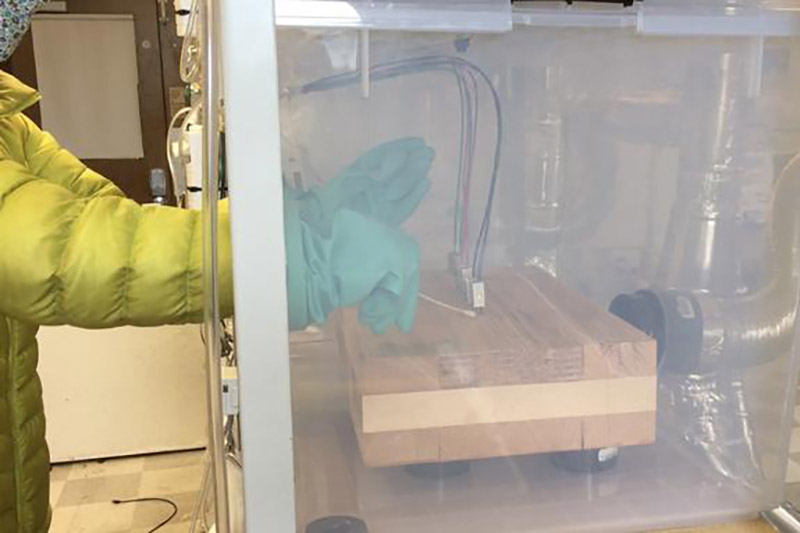

Swab collects a microbial sample from a block of cross laminated timber

© University of OregonWork from the University of Oregon (UO), USA, has found that exposed wood can resist microbial growth after it briefly gets wet. During the study, wood samples tested lower for levels of bacterial abundance than an empty plastic enclosure used as a control.

‘People generally think of wood as unhygienic in a medical setting,’ says Assistant Professor Mark Fretz. ‘But wood actually transfers microbes at a lower rate than other less porous materials such as stainless steel.’

In a recent study published in Frontiers in Microbiomes, they share their discoveries about the effects of moisture on surface microbes and volatile organic compound emissions from mass timber.

‘We wanted to explore how mass timber would stand up to the everyday rigours of healthcare settings,’ says Research Assistant Professor Gwynne Mhuireach. ‘In hospitals and clinics, germs are always present and surfaces occasionally get wet.’

During the research, blocks of cross-laminated timber were sealed in disinfected plastic boxes to create a micro-environment with carefully controlled temperature and humidity. In order to simulate a healthcare setting, air was filtered and exchanged at rates similar to hospital codes.

The blocks were sprayed with tap water, inoculated with a cocktail of microbes commonly found in hospitals, and samples taken over a four-month period. An empty plastic box was used as a control.

The researchers compared coated and uncoated wood samples under three types of water spray events: just once, every day for a week and daily over four weeks.

The results of the study indicated wood is effective at inhibiting bacteria and revealed clues about wetting that will inform future research and development, Mhuireach says.

The empty plastic control box had greater viable microbial abundance than the wood samples, over time. Wetting the wood blocks reduced the abundance of viable bacterial cells, with no discernable difference between coated and uncoated specimens.

During wetting, microbial composition reflected what’s common in tap water over the hospital pathogens the team introduced.

Wood’s ability to inhibit the spread of pathogens may stem from pores that trap bacteria or antimicrobial chemical compounds that occur naturally. It could also result from wood’s capacity to absorb moisture.