Unearthing resources

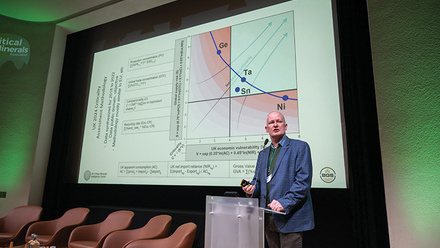

REECON-UK brought together the rare-earth global supply chain to explore recent geopolitical developments, technological advances and resource challenges.

The overarching theme underpinning the REECON-UK event on 6 June at the University of Oxford, UK, was that while we do not need a lot of rare-earth elements (REE) in individual components, things simply do not work without them.

The challenges the UK and other countries face is in supply and refining the metals – few places globally do this. China holds the greatest share of the global REE market, putting the raw materials on the UK and other countries’ hit list for critical minerals.

'The Middle East has oil, China has rare-earths,' said Deng Xiaoping in 1992, who served as the leader of the People’s Republic of China from 1978-89. Professor Frances Wall of Camborne School of Mines, UK, acknowledged we are wrestling with the truth behind this quote.

David Brown, from the University of Birmingham, UK, Magnetic Materials Group, exemplified the challenge in producing permanent magnets, crucial for our daily lives but with no credible rare-earth replacement for their production. He noted there is a huge market for a non-China supply chain.

This year alone, the Materials World team has reported on partnerships to target rare-earths mining in countries such as Greenland and Saudi Arabia. While Lynas Rare Earths claims to be the only commercial producer to have separated heavy rare-earth products outside China, and Canadian firm Cyclic Materials has invested in its first US facility to separate permanent magnets and recycle REEs from end-of-life products.

Not to mention, the extensive media coverage around President Trump’s efforts to secure rare-earths supply. As Materials World was going to press, a new rare-earth mine has been found viable in the US for the first time in 70 years.

And a project to extract minerals from volcano plumes, and another to extract them from mining waste, were among nine innovation partnerships that were awarded £3.5mln from Innovate UK in 2024 to boost the UK’s rare-earth supply chain.

In this context, Ivan Lima, Investment Lead for UK critical minerals at the Department for Business and Trade, was clear that the upcoming Critical Minerals Strategy provides an opportunity to articulate the UK’s vision for critical minerals in the future, building on experience from the 2022 strategy.

Time to mature?

Dr Vicky Mann, a Research Fellow in Metallurgy and Materials at the University of Birmingham, acknowledged that magnets are the single most expensive import cost for the automotive sector and believes recycling would reduce reliance on the REE supply chain and mitigate cost pressures and volatility. Despite this, the UK currently recycles almost no REEs.

But the UK REE ecosystem is certainly maturing, revealed Mann. She referenced Belfast, Birmingham, Elesmere Port, Southend and Sheffield as a recycling corridor for REEs that is beginning to establish itself.

Indeed, HyProMag, a spin-out company from the University of Birmingham, is commercialising a patented hydrogen process of magnetic scrap technology.

This involves a combination of mechanical agitation and hydrogen decrepitation to liberate neodymium-iron-boron material from end-of-life components. This process was scaled up at Tyseley Energy Park in 2023 – now 400kg of neodymium is being recovered per batch.

Unlocking this stream of material presents an alternate feedstock from primary-mined REEs to produce new magnets.

The University of Birmingham is also the UK lead in the EU Horizon-funded project REEsilience, which is aimed at building a resilient and more sustainable supply chain for rare-earth magnets.

It is coordinated by the Institute for Precious Metals and Technology at Pforzheim University in Germany, with a consortium of 18 partners from 10 European countries.

They are categorising REEs by geographic locations, quantities, chemical composition, ethical and sustainable indicators, ramp-up scenarios and pricing, considering all value streams from virgin to secondary material, to ensure fewer dependencies on non-European economies.

Using a new software tool, they seek to identify optimum mixing ratios using maximum secondary materials for high-tech applications.

Combined with new and improved technologies for alloy production and powder preparation, the yield and stability of processes will be further enhanced to increase the proportion of secondary materials in magnet production, while reducing waste, environmental impact and energy consumption linked with virgin material acquisition.

Mann believes the lack of focus and progress in recycling these materials before now has been a matter of money. There has not been enough government investment, although she acknowledged some design element and access issues.

She also believed there needs to be more acceptance that recycled products are as good as primary sources.

Among other initiatives, Less Common Metals (LCM), UK, leads in the Industrial Scrap-to-Magnet project, which also received funding from above-mentioned Innovate UK Circular Critical Materials Supply Chain programme.

It aims to develop high-quality magnets using 100% recycled and fully traceable REEs. The project will focus on reclaiming pre-consumer industrial scrap from magnet manufacturing and material processing stages, which account for 36% of valuable REE content, says the firm.

For over 30 years, LCM has used several reprocessing routes to recycle materials and is dedicated to a closed-loop circular economy.

Geography of the geology

LCM also reports to be the only commercial facility outside China, or that is not Chinese owned, producing neodymium metal and neodymium praseodymium master alloy by molten salt electrolysis.

All raw materials for its light rare-earth processing are reportedly now sourced independently of China, and they have expanded this capability to include heavy rare-earths as well.

Grant Smith, Chairman of the company, noted that they do not anticipate much competition because of the low profits in the market. He asserted that, despite its importance, it is a small industry and many of the majors are not interested in it.

As an indication of how difficult the industry is, he cited the fact that the Indian Government has 'done nothing' with its REE company for nine years.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Government saw the potential earlier on, with a 10-year industrial policy plan to transform China’s manufacturing sector and economy in 2014.

The strategy focused on the production of electric vehicles (EV), advanced robotics and artificial intelligence, to create high-end jobs as evidenced by the IEA statement: 'China’s clean energy manufacturing sectors employ roughly three million workers, accounting for 80% of solar photovoltaics and EV battery manufacturing jobs globally'.

Nevertheless, Smith shared, 'I go to Washington and I say ‘calm down’,' because LCM has the stocks and capability he says and Lynas has the supply chains.

And the good news, he said, was that the UK punched above its weight in terms of applications. He acknowledged an attitude that we cannot compete with China, but believes all they need is demand and a supply of reasonably priced materials and 'we’ll take anyone on'.

Responsible sourcing is key however. Sam Broom-Fendley, Lecturer in Geology at the University of Exeter, UK, gave the positive example of the Songwe Hill project in Malawi – a carbonatite-hosted, rare-earth deposit, where full drilling was proposed last year and it received US$2bln in funding as of May 2025. But there are concerns surrounding how the drilling will affect drinking water.

Dr Kathryn Goodenough of the British Geological Survey stated, 'We ought to be prepared to pay for that responsible sourcing'. She asserted that Europe can provide all the REEs it needs.

Professor Martin Smith, University of Brighton, reminded the audience, 'The resources are where they are'. There are none in the UK, he said. Goodenough countered that there are very small amounts in the Highlands, but they were not at economic scale. And there are some in Wales.

She believed advanced tools are needed to identify mineralised deposits, while Professor Adrian Finch, at the University of St Andrews, highlighted that we now know a lot more to scope mineral content before we drill.

Wall noted countries are saying they don’t want the old model of digging and shipping ore. And Dr Robert Pell, founder and CEO of Minviro, added that there needs to be a different definition of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for this purpose.

He focused on how weighting within LCAs can bring certain factors to the fore. Although he believed measures could be improved, he did not feel that consumers were asking the right questions.

Wall believed that consumers need to make sustainability a more important criteria for purchasing. Meanwhile, Professor Peter Hopkinson, speaking for UK Research and Innovation, was interested in reducing demand.

Robert Bowell FIMMM, Corporate Consultant (Geochemistry) at SRK Consulting, believes future mining operations will have to expand what they consider ‘valuable’, for example, most gold ores are analysed for gold but probably hold lots of other valuable minerals.

Scramble for minerals

The Senkaku incident in the early 2000s saw China start speculating to a price spike in rare-earths, explained David Merriman of Project Blue. In 2011, there was a crackdown on illegal producers in China. This development provoked a drive to substitute rare-earths and design them out.

New environmental regulations in 2017 in China also created volatility in the market. The Chinese Government reportedly deliberately pushed prices back down by demanding the release of inventories in 2022.

Merriman then turned to what rare-earth pricing might look like in the rest of the world outside China, and alluded to the reality that although people talk about wanting an improved ecological footprint, there does not seem to be a willingness to pay a premium.

When speaking of the EV market, he says, 'To assign extra purchasing costs to those products is really not palpable to many of the purchasers'. This sits within a context of rare-earth costs climbing.

There is the need to build a suitable downstream demand for higher pricing.

This led to Dr Amir Lebdioui, Professor of the Political Economy of Development at the University of Oxford, to share his perspective.

He referenced the experience of Fritz Haber and the crashing of the Chilean economy as an example to illustrate the phenomena of the fluidity of what is a critical material, in this case the material in question was nitrate.

'We consider rare-earths to be part of critical minerals, but criticality is highly dependent across time and space. What’s critical today might not be critical tomorrow. What’s critical in one place might not be critical in another place…We rarely ask it’s critical for whom, based on who produces it and who consumes it.'

While recycling can develop to affect demand, so too can rethinking public transportation to lower demand.

He ambitiously looked towards a global system for negotiating prices. Pointing to the problem the former US President Biden had in localising or negotiating with China.

He saw benefits in cooperation and even applied John Nash’s game theory model to the scenario. Saying it was not in China’s interest to have a concentration of assets, asserting that they do not want to be in isolation, but interdependent. He reminded the audience that there was scope for cooperation as REEs were not weaponised.

Merriman concluded his contribution saying REEs are currently very concentrated, so a single event could cause a supply chain shock like what he described in the Senkaku incident.

As Bowell stated, 'What makes you think you’re going to be better the second time round, when you have less of the resource.'